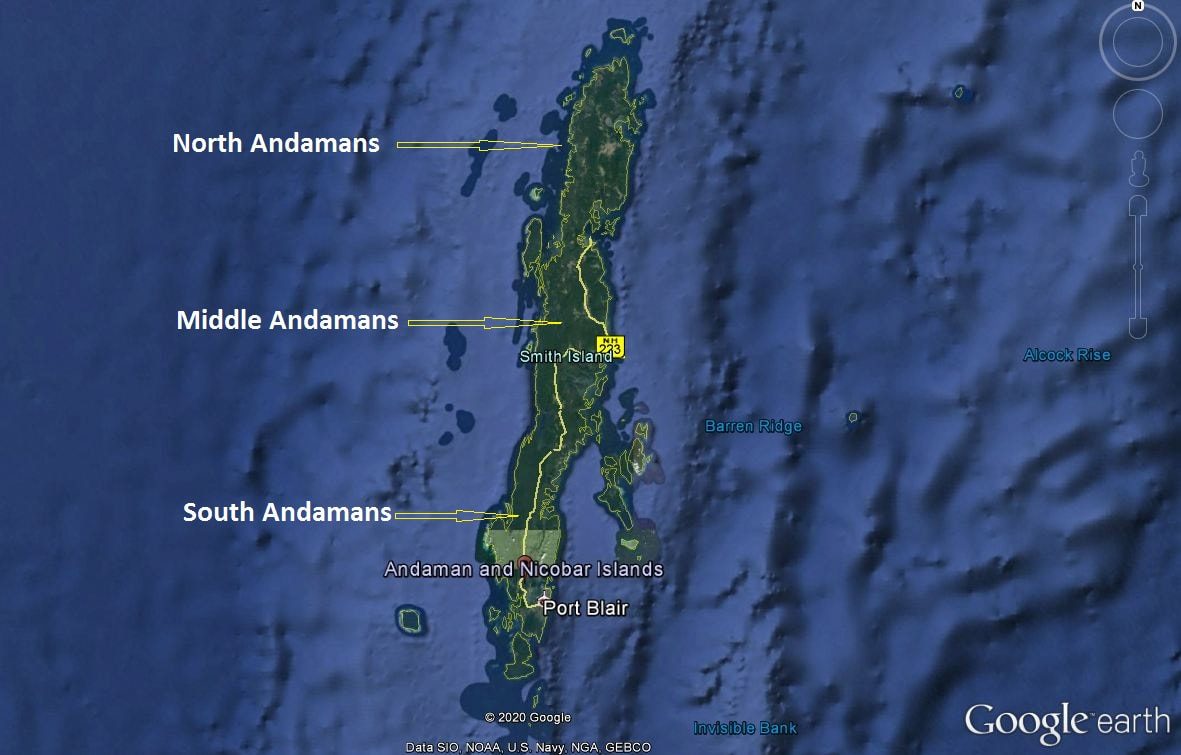

Andaman and Nicobar Islands are located in a unique biogeographic position. They are located at the eastern part of the Bay of Bengal and more connected to Burma and Indonesian Archipelago thus the biodiversity in these islands shows a strong affinity to the Sundand of Southeast Asia. Also, as these are an island group separated from the continental mainlands, speciation has occurred abundantly resulting in numerous endemic forms within the islands. The 150 km long 10 degree channel (named such as 10 degree line of latitude lies across it) between the Andamans and Nicobar islands have also facilitated more geographical isolation leading to further speciation, producing endemism even within the two island groups. Saddle Peak is the highest peak in Andaman and Nicobar islands and that’s where we were heading on the fourth day of our expedition.

We had a rough evening on our day 3 (see Expedition Diaries 1.1). On our way back from the Kalpong Dam, we came across a heavy rainfall and were drenched by the time we reached our accommodation. However, that wasn’t enough to lower our motivation. Following morning, 18th August 2017, we left Diglipur again, heading towards the Saddle Peak Mountain which is located near the western coast of the North Andaman Island and is 732 m high.

We had a rough evening on our day 3 (see Expedition Diaries 1.1). On our way back from the Kalpong Dam, we came across a heavy rainfall and were drenched by the time we reached our accommodation. However, that wasn’t enough to lower our motivation. Following morning, 18th August 2017, we left Diglipur again, heading towards the Saddle Peak Mountain which is located near the western coast of the North Andaman Island and is 732 m high.

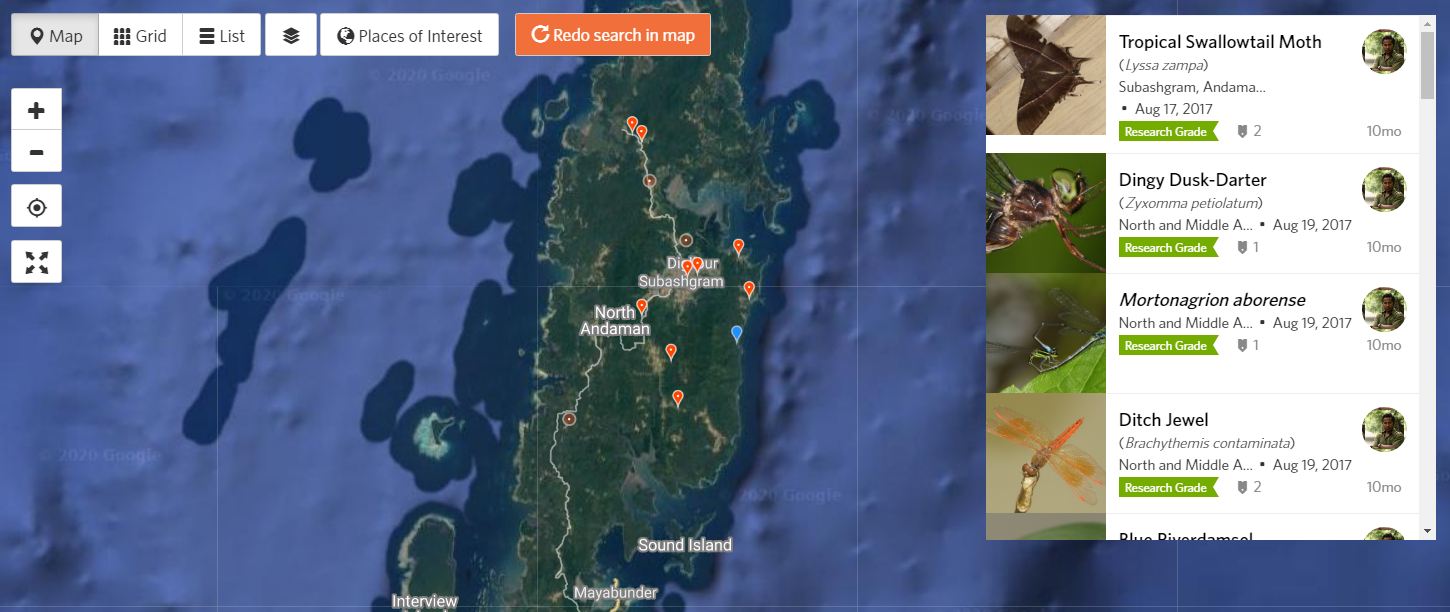

| We checked few places on our way to the Saddle Peak for birds and dragonflies. We came across several roadkills of Andaman Keelbacks (Xenochropis tytleri). Considering the low level of motor traffic and the high encounter rate of road kills, it must be very common in the island. The Saddle Peak trail starts at the forest edge, runs along the coast and turns inland starting the ascension towards the peak. We could only explore the foot hill area as clouds were gathering and lowered the number of dragonfly sightings. We observed several new additions to our ododnate list of the trip such as Pygmy Skimmer (Tetrathemys platyptera), Ramburi Red Parasol (Neurothemis ramburii) and Red Glider (Tramea transmarina). We also encountered a mixed-species bird flock with many Andaman endemics including Andaman Shama, Andaman Drongo, Andaman Bulbul. Bay Island Forest lizards were very common in the forest area. |

| While heading back, we came across a very interesting dragonfly. It was sitting on a fallen branch in a shady place. It was dark blue in colour with pale anal appendages. Prosenjit managed to get a photograph but the dragonfly flew away without giving us an opportunity to examine the details. We were puzzled by this mysterious Skimmer thus we looked for it for sometime but could not find it again. Later we checked the available literature with no positive identity, leading us to the conclusion that it should be something new. Three years later, in May 2020, this mysterious species was taxonomically described by Matjaž Bedjanič, Vincent Kalkman and K. A. Subramanian as Orthetrum andamanicum (Andaman Skimmer). It was great knowing that we could have a glimpse of this species, unknown to science at that time, during our short expedition to the islands. Our main destination on the following day was the Mud Volcano located near Shyam Nagar. That was the northern most locality we visited during the trip. Though we didn’t encounter any new odonates during the visit, several new birds including Bar-bellied Cucukooshrike, White-bellied Woodswallow, Spot-breasted Woodpecker and Blue-eared Kingfisher were added to the list. It was our last day in North Andamans. We ended our field work early and headed back to the accommodation to prepare for the return trip. Though the regular rainfall during the days did not support our work, all of us enjoyed the experiences we encountered in North Andamans. It was a land of forests, a rich biodiversity and kind people. We experienced this couple of times. On two days during our explorations in rural areas, we couldn’t find any eateries and when we talked to the local people, they prepared meals and offered us with no hesitation. It was simply, a gesture of humanity. |

| We left Diglipur in the evening of 19th August and reached Port Blair the following morning. After a rest, we went to the Chatham Jetty and took a ferry to reach the Mount Harriet National Park, the highest point in South Andamans (383 m). It was a short visit, but we recorded few more endemics including Andaman Green Pigeon and Andaman Wood Pigeon. On the last day of our trip, we visited the Zoological Survey of India Port Blair office and met the ZSI scientist Dr. Tamal Mondal, a friend of Prosenjit, and he introduced us to his fellow scientist S. Rajeshkumar, who is working on the Odonata of the islands. We had a great discussion, shared our observations and learnt a lot from his experiences in the islands. He also showed us some amazing species he had encountered especially during his work in the Nicobar islands. After that, we visited few souvenir shops and head back to the hotel for final packing before we leave the islands. In the afternoon, amidst continuous rainfall, we reached the Port Blair airport and left the splendid Andaman Islands ending our eight day trip. |

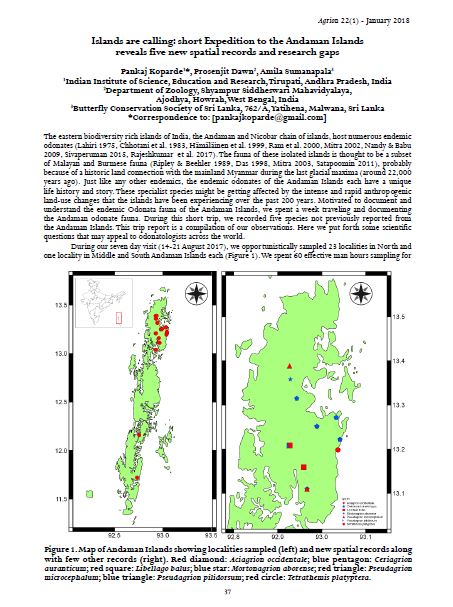

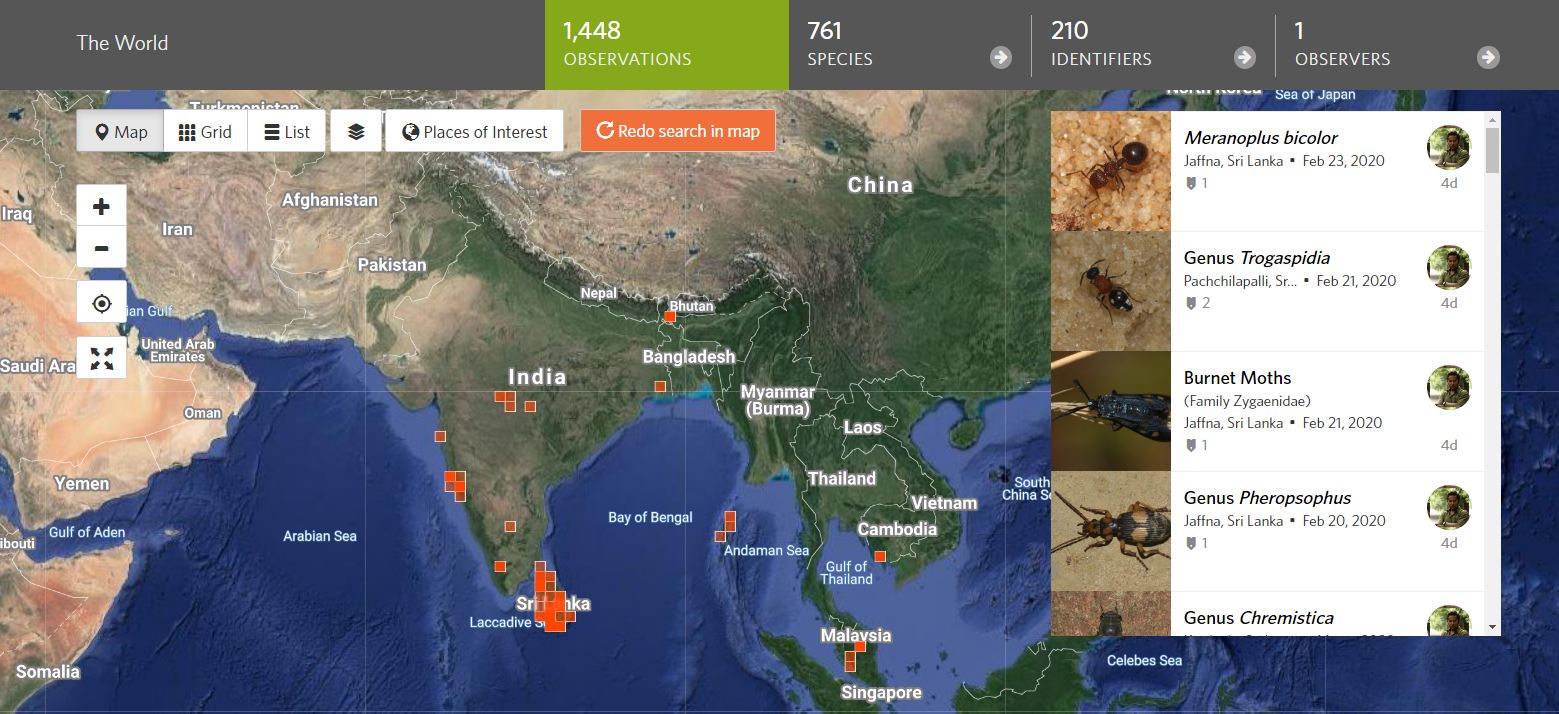

| The main objective of the trip was to explore the odonates of Andamans in its changing landscapes. While doing so, we recorded 35 Odonata species in 23 different localities, despite the unfavorable weather conditions that prevailed throughout the expedition. These also included four species that were not documented from the Andamans prior to that. 11 new additions to my Odonata life list and 26 to my bird list were also recorded during the expedition. Few months later, after compiling all our observations and identifying what we observed during our explorations, we submitted a short manuscript on our findings to Agrion, the newsletter of the Worldwide Dragonfly Association. Koparde, P., Dawn, P. and Sumanapala, A. (2018). Islands are calling: short expedition to the Andaman Islands reveals four new spatial records of Odonata and research gaps. Agrion: Newsletter of the Worldwide Dragonfly Association. Vol. 22(1): 37-41. Pdf. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed